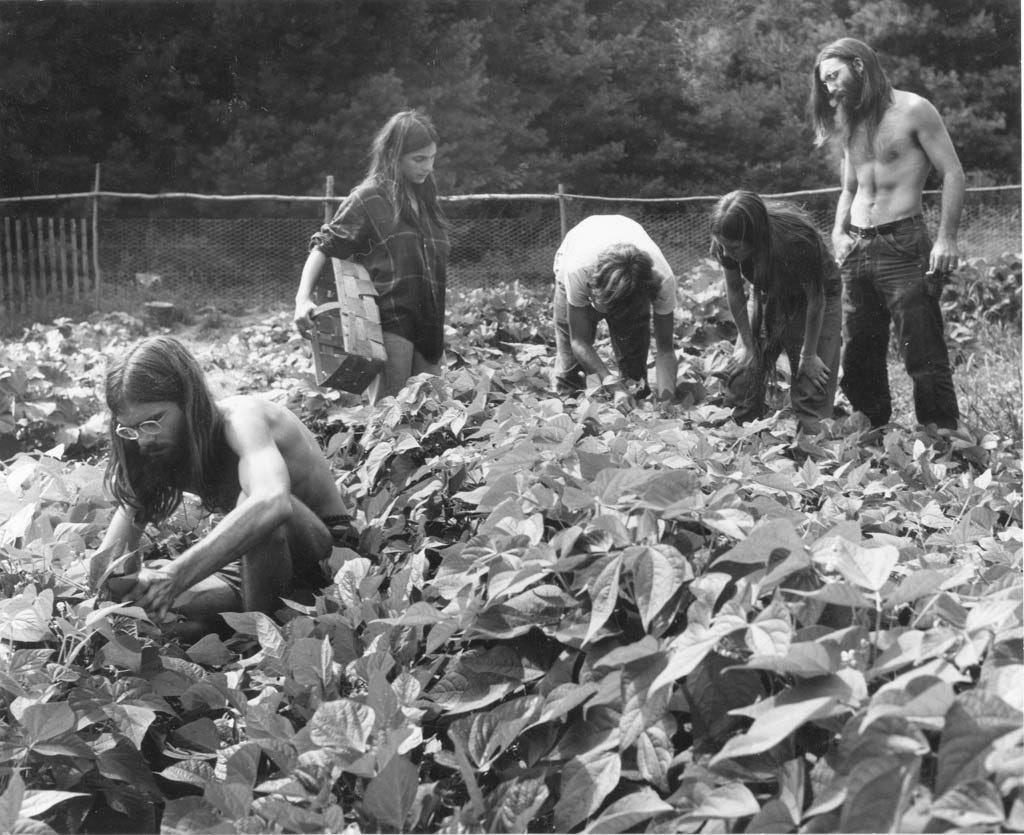

What was once a fringe interest of hippies and back-to-the-landers in the 70s, the organic food movement has quickly grown in popularity across all demographics over the past decade. From my perspective, several factors have contributed to this new widespread allure: lawsuits filed against agrochemical companies like Monsanto for their role in directly causing cancer (non-Hodgkin's lymphoma), a desire for more nutrient-dense food, concern for the welfare of farmers, planetary and soil health, a longing for more traditional ways of life, and an effort to dismantle and opt out of fragile outdated corporatized systems driven by the exposure of fragile health and supply chains during the pandemic, among other things. We all have our reasons for prioritizing organic food, and this booming cultural phenomenon has become both a blessing and a curse. Because we have a consumer-driven market, the demand for organic food has increased its availability and forced companies to adapt to consumer demand. As the saying goes, “you vote with your dollar.” Additionally, the conversation around the benefits of eschewing synthetic pesticides and herbicides, like increased land resiliency, improved soil health, and greater crop yield, has also opened the minds of conventional farmers who have begun taking the leap to transition their farms to low-input, organic, or even regenerative models. Fewer folks are inadvertently exposed to carcinogenic pesticides and herbicides like glyphosate, and produce grown without these agrochemicals contains more nutrients like antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals. These are some of the most significant benefits of the growing interest in organic. But as I said, there are also downsides. As with any growing interest, the organic movement has been co-opted by corporations whose priority is profit and the “organic” label is slowly losing its meaning. We’re seeing ultra-processed cookies, chips, and candy labeled “organic,” not because they’re thinking more critically about farming or food production, but because they know it will increase their profit. We’re also beginning to see farms producing organic food, but operating more similarly to conventional industrial farms than small scale family farms, which again, is a less-than-altruistic profit-driven choice. How can we, as consumers, differentiate between organic labels and make choices that most align with our values? It begins with education around what organic means and what organic doesn’t mean.

Before organic certification existed, “organic” farming was just called farming. There was no need to distinguish because that was simply the way it was done. Before the efforts to increase yield to “feed the world,” farmers grew food for their communities copacetic with nature’s rhythms: companion crops, diversity of species, fertilizer from their animals, natural aeration of the soil from earthworms, cross-pollination from bees and butterflies, and cover crops. With these components came increased water holding capacity, mineral-rich soil, and a robust carbon sink, benefitting the planet and all organisms involved in this synergistic ecosystem.

In the mid-1800s, modern industrial agricultural practices began with the foremost goal of increasing crop yield to support a growing US population. This is where we began seeing a shift toward mono-cropping (large fields of single crop varieties) of hybrid crops owned and sold by individual corporations, the use of fossil fuel energy and synthetic fertilizers, and increased use of machine-power versus man-power. I always like to emphasize that this was all done with good intention, but it slowly created a behemoth far more powerful than we could’ve imagined.

Modern industrial agriculture catapulted further in the 1940s and 50s during the Green Revolution. Again, this was a well-intentioned movement to initiate greater crop yields (specifically wheat and rice) in food-insecure developing countries with the use of hybridized high-yield grain varieties like dwarf wheat, chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and controlled irrigation, and these practices spread globally throughout the following few decades.

The Green Revolution introduced a charged specific word to associate with this style of agriculture: “global.” Focus was no longer on feeding our immediate community, but rather on feeding the world, and by any means necessary.

The first organic certification system in the country was introduced in Maine in 1972 to distinguish small scale food producers and back-to-the-landers from their industrial ag counterparts, and this sparked other states to begin developing their own organic standards and certification methods. National standards were developed by the USDA in the 1990s for produce and processed food products alike. Organic certification has slowly turned into a behemoth industry of its own. To acquire an organic certification, it takes much more than organic farming practices. In addition to farming without the use of synthetic pesticides and GMO crops, it also requires loads of paperwork, a minimum annual profit, review and inspection, and an annual fee of thousands, in some cases tens of thousands of dollars. Many of these requirements are prohibitive for small family farms whose practices are beyond organic, but are easily completed by large corporatized farms whose practices might not be as benevolent.

What are you guaranteed when you buy organic? Non-GMO, no synthetic pesticides or herbicides, and in animal agriculture, no growth hormones or antibiotics. Why is this important? The primary reason I advocate for consuming produce grown with organic practices is to reduce exposure to harmful pesticides and herbicides, namely glyphosate, the active ingredient in the weed-killer Roundup.

Glyphosate has been classified by the EPA as a “probable human carcinogen,” class 2A, and impacts mitochondrial function, metabolic health, endocrine function and fertility, integrity of the gut lining and the bacterial composition in the microbiome, liver function, immune function, cognitive function, and most notably, has been linked to cancer (non-Hodgkin's lymphoma).

Occupations that require heavy exposure to glyphosate (school and park groundskeepers, industrial conventional farm workers, landscapers, children whose families live near heavily sprayed areas) are disproportionately affected by high rates of cancer. Not only is glyphosate found on our food, but its prevalence in our food system has allowed it to make its way into our water, air, and rain. Not only is Roundup sprayed on crops, but “Roundup Ready” GMO crops have been developed to withstand heavy use of the herbicide. Roundup is most often used as a weed-killer, but it’s also used to desiccate many grains upon harvesting to dry them out before storage to inhibit mold growth. This is a practice often applied to conventional oats, for example.

Certain crops are more likely to be sprayed than others: grains, beans and legumes, tomatoes, spinach, berries, bell peppers, grapes.

Cheerios, for example, are one of the most glyphosate-laden processed foods on grocery store shelves. Other important items to consider buying organic with regards to the above list are oats or oat-containing products (granola), beans and legumes and thus hummus, corn, and other grains. The practice I advocate for most strongly is to shop at your farmers market and buy as much as you can from local farmers, ranchers, and food producers. But what if they’re not certified organic? Let’s get into that…

When I visit the farmers market each week, I almost always hear shoppers ask farmers if their produce is organic, and because they may not be able to allocate annual funds to receive official certification, they must answer no despite farming organically anyway. Before the farmers can explain this, the customer puts the produce down and looks elsewhere for the “organic” label they’ve been conditioned to value above all else. More important than the organic label is engaging in conversation with your farmers. Before walking away after hearing they’re not certified organic, consider asking more about their practices.

“What sorts of pest management practices do you use? How do you fertilize? How do you control weeds? Are you growing in soil or in hot houses? How soon before market day do you harvest? What do you supplement your animals’ feed with? Do you ever use antibiotics or hormones? How frequently are the animals moved to new pasture?”

The answers to these sorts of questions will give you a much clearer picture of their practices than an organic certification. It might feel intimidating asking questions, but farmers and ranchers love what they do and are more than happy to talk to you about it! Some of the most dedicated land stewards I’ve ever met aren’t certified organic, but farm in a much more naturally aligned way than the “industrial organic” farms (as Michael Pollan calls them) that you’ll find in your grocery store.

What are you not guaranteed when you buy organic? You’re not guaranteed fair treatment of and compensation for farm workers, diversity of crops, attention to soil and environmental health, or the use of “natural” pesticides and herbicides.

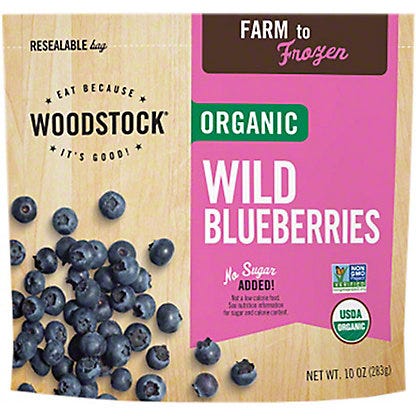

When folks buy a bag of organic frozen berries or a plastic box of organic spinach from the grocery store, in their mind’s eye they see a pastoral landscape with green rolling hills and Old McDonald with his wicker basket harvesting their fruits and vegetables one by one. This is due, in part, to the positive association we have with the word “organic,” but also due to industrial organic farms literally painting this scene for us on their packaging despite nothing being further from their reality.

Because of a lack of understanding around agriculture and food production, the Woodstock Organics and Cascadian Farms and Earthbound Farms of the world can easily manipulate consumers into believing they’re supporting a small family farm by buying their bagged salad greens.

Let’s take Earthbound Farms, for example. Their website tells of their humble beginnings selling bags of mixed lettuces at a roadside farm stand. They’ve since grown into a $350 million company. Although they technically use farming practices that meet the USDA organic standard, they produce food on an monocrop industrial scale and operate more similarly to conventional farms. In Michael Pollan’s book, Omnivore’s Dilemma, he details the inhumane treatment of their migrant farm workers that no one would imagine taking place on an idealistic organic farm: for example, wearing bright blue bandages on their hands that contain a metal chip so they can be easily spotted and picked out of the greens as they’re run through a metal detector before boxing and bagging.

But because of the weight we’ve placed on organic certification, I’m sure there are folks out there who wouldn’t think twice before buying a box of Earthbound Farms lettuce but would walk away from the stand of a small farmer who doesn’t have the means to go through the USDA organic certification process. But what they don’t realize is that the lettuce from that farmer is fresher, contains more nutrients, was harvested by that farmer (or fairly treated farmworkers) the day prior, and that their practices are improving the health of the soil.

USDA organic labeling isn’t a perfect system, but it’s what we’ve got. If you’re shopping at the grocery store, I think buying organic as much as possible is of the utmost importance. If not financially feasible, consider prioritizing grains, beans and legumes, tomatoes, spinach, berries, and bell peppers and processed foods that contain these crops. But your best bet? Buying local, regardless of organic certification, and having conversations with the folks growing your food. Supporting folks stewarding the land, whose primary focus is on human and planetary health above profit, will help shape the food system we want to see. If we can give our support, energetically and financially, to the little guys instead of the big guys, we can play a role in creating a more resilient, regenerative food system.